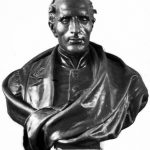

In 1990, President H.W. Bush signed ADA into law

Just over a half century ago marked the passing of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, amended by Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. Twenty-five years later and 27 years ago, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) passed with bipartisan support in both chambers of Congress and was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush. The date was July 26, 1990. The title sheet of the document read “An Act: To establish a clear and comprehensive prohibition of discrimination on the basis of disability.”

It is worth noting that earlier in the week, people around the world celebrated the International Day of Persons with Disabilities. Though Mr. Bush originally expressed doubts about the act, his being open to compromise and act in the interest of all Americans was evident here.

In its Morning Edition talk show, NPR hosted a thoughtful memorial on Mr. Bush’s legacy on behalf of persons with disabilities. Though President Bush has now been laid to rest, his legacy continues!

A Quick Look Back

According to the federal government, ADA “…prohibits discrimination and guarantees that people with disabilities have the same opportunities as everyone else to participate in the mainstream of American life.” Specifically, ADA:

- Forbids discrimination in employment on the basis of any disability

- Requires full access to government facilities and services, including public transportation

- Full access to all places of public accommodation, including commercial establishments

- The ability to use all forms of telecommunications technology.

ADA also sets standards on accessibility, for example wheelchair ramps, entrances, and playgrounds.

ADA gained strength in 1999, after a Supreme Court case, Olmstead v. L.C., ruled that people with mental illness have a disability. Often known simply as “Olmstead,” the law states that people with cognitive disabilities have the right to live in least-restrictive setting, often community residences, rather than state-mandated institutions.

The Background

For the first 150 years of U.S. history, life for most people with disabilities was fraught with misery and challenges. Most people with cognitive disabilities were consigned to state institutions for their entire lives. In 1887, a pioneering investigative reporter named Nelly Bly wrote Ten Days in a Mad-House, exposing the horrors of these asylums. People like Helen Keller were the exception! In 1899, a lady named Elizabeth Farrell left her comfortable life in Utica, NY, to travel to the slums in New York’s Lower East Side. There, she established the Henry Street School, teaching children with severe disabilities practical skills. Her tireless advocacy would form the foundations of the special-education laws of today.

Disability rights in employment in the U.S. go back to 1920, when President Woodrow Wilson signed the Smith-Fess Act, which provided for World War I veterans disabled in action. However, this was also the time of the eugenics movement—forced sterilization prevented “feebleminded, insane, depressed, mentally handicapped, and epileptic people” from having children. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 called for sheltered workshops for all people with disabilities, not just the blind. Yet, there was still a need for a law offering access to all people with disabilities to all aspects of life. Former Iowa Senator Tom Harkin set out to correct that when he authored ADA.

Earlier this year, we acknowledged another disability advocate, Elizabeth M. Boggs. More than two-thirds of American adults with disabilities are still “striving to work,” according to a national employment survey. Disability advocates are trying to change that, in their effort to fulfill the promise of ADA.