With humor, Haben Girma in her 2019 memoir shares how she defined her life, on her terms.

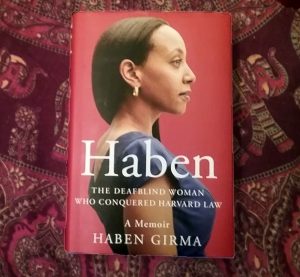

Haben Girma has been in the news a great deal. And with good reason. A notable piece recently appeared in The Guardian, and she was featured in a BBC interview. Saturday, January 4, was World Braille Day. Last year, she published a remarkable memoir, Haben: The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law. We review the book here and, as disability advocates ourselves, are happy to recommend it.

“Communities designed with just one kind of person in mind isolate those of us, defying their narrow definition of personhood.”

“Hindsight may be 20/20, but 20/20 is not how I experience this ever surprising world.”

As a middle school student, Haben Girma learned she was failing her history class. She faithfully completed each of her assignments – or so she thought. What happened was that her teacher often wrote the day’s homework on the board and announced them from the back of the rook. As a Deafblind person, neither message reached her. Haben learned early in life how important it is to be a self-advocate. Then, again, as she describes early in her memoir, Haben’s East African parents were an excellent example for her. “My parents found a way through injustice, and I will, too.”

One aspect of self-advocacy is convincing the world at large of what she is able to do. That included convincing her well-meaning and supportive but protective parents that she take on the challenge of traveling to Mali with her high school peers to help build a school, as she describes in the cleverly titled chapter “Dishing Up Trouble.” Then, once in the West African country, she was determined to show she could be a full participant in the effort. Haben does note that her parents otherwise wanted Haben to do anything non-disabled children can do.)

As an undergraduate at Lewis & Clark College, Haben again had to advocate for herself. She found that one of her greatest challenges was not acing that final exam, but simply being able to order a meal at the cafeteria, as the menu was inaccessible to her. Haben’s solution was simple: the manager of the cafeteria needed only to send her the menu as an email text attachment; her screen reader, an assistive tech device that converts text to digital braille, would do the rest. The greatest obstacle was convincing the manager to overcome his own laziness and accept her disability. Says Haben, “Blindness is nothing more than a lack of sight.”

More than being able to observe her vegetarian diet, Haben learned that by advocating for her own rights, she was helping everyone. (Curb cuts benefit people beyond those who use a wheelchair.) She set herself on a course of becoming a disability rights attorney.

Through her hard work and determination, Haben was accepted at Harvard Law School. At that time, Haben’s hearing was deteriorating. In addition to becoming acclimated to an extremely heavy course load, Haben had to work with interpreters and new forms of assistive technology to be able to simply gain access to the material. One system Haben helped develop was a wireless interface, where a sighted person types a message on a standard QWERTY keyboard; the message then appears on Haben’s device, an adapted computer called a BrailleNote, which features a tactile screen “screen” whose braille letters change with the message. “The familiarity of the keyboard provides an opening that allows me to help people feel comfortable despite our differences.”

As an attorney, Haben worked for a firm representing the National Federation of the Blind. The case involved whether a place of accommodation applies to a website, such as Scribd, an online library of more than 40 million books and documents. That the word “place” did apply to websites and apps was a notable vindication of the essence of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA). As a result, most online businesses, via websites or apps, know the tremendous opportunity being able to reach millions of disabled users presents, aside from it being the right thing to do. Shortly afterward, Haben was invited to the White House to meet President Barack Obama and other disability activists, including Tom Harkin, the former Iowa senator who championed the passage of ADA. This meeting, captured in several famous photos, is one of the highlights of the book.

As many blind people have done, Haben developed an astute spatial and tactile awareness. With that, Haben loved dancing. While working at a gym, a sighted customer reported that she could not get her treadmill to work. After checking the front panel, Haben felt her way down the machine and found a small switch at the base. “I didn’t even see that switch,” the customer said. “I didn’t see it either,” responded Haben. “Sometimes tactile techniques beat visual techniques,” she observed.

Beyond school and career, Haben rarely passed the opportunity to embrace life’s adventures. The outdoors adventures Haben she describes range from climbing and iceberg in Alaska to surfing in Hawaii. Says Haben, “My life belongs to me. I can’t surrender to feeling trapped.”

Ever positive, Haben seeks acceptance. After all, she accepts who she is. “I like my Deafblind world. It’s comfortable, familiar. It doesn’t feel small or limited. It’s all I’ve known; it’s my normal.” Haben invites the reader to enter her world and experience it as she does. “In a sighted, hearing society… I’m disabled. They place the burden on me to step out of my world and reach into theirs.” With her thoughtful memoir, Haben invites anyone who will “listen” into hers. And, throughout, Haben’s positive outlook shines. “At some point in my childhood, I discovered the goodwill of bringing laughter into people’s lives,” says Haben. “Humor draws people in, paving the way for meaningful connections.”

Girma, Haben. Haben: The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law. New York: Twelve, 2019.

277 pages

ISBN: 978-1-5387-2872-7 (hardcover), 978-1-5387-2871-0 (ebook)