“A black woman can invent something for the benefit of humankind”

– Bessie Blount (1914-2009)

Windshield wipers, the automatic transmission, electric turn signals. They are all standard equipment on our cars, devices we all take for granted. And let’s not stop with the traffic signal! What is less well known is that they are all results of the imaginations of African American inventors. This week for Black History Month, we are exploring and highlighting the lives of notable African American men and women with disabilities or involved with those who do. We start this week, for or Assistive Tech Tuesday, with a very interesting African American inventor in the field.

“A black woman can invent something for the benefit of humankind”

– Bessie Blount

For many people, a seemingly mundane experience can have a transformative impact. Such was the case with Bessie Blount Griffin. Born left-handed, in 1914, an early school teacher would rap her on the knuckles for using the “wrong” hand. To “adapt,” Bessie took on the challenge, teaching herself to use both hands in writing. And despite the initial negative experience, Blount loved going to school, continuing with nursing training in Newark, NJ, and Panzer College of Physical Education and Hygiene in East Orange.

Wanting to use her training to help people during World War II, Blount worked with amputees. There, she believed that the best way to help people is to help them help themselves. As such, she saw the need for an apparatus for these veterans to feed themselves. She built her device around a rubber tube to dispense liquefied food one mouthful at a time; the individual controlled this through movements of the jaw. The Veterans Administration at the time was not interested in purchasing her invention, so she donated the rights of her inventions to the French government. Over the years, devices based on her invention have been in use in military hospitals across France.

Follow-Up Inventions

Bessie Blount invented this assistive technology device to offer people with physical disabilities independence by helping themselves.

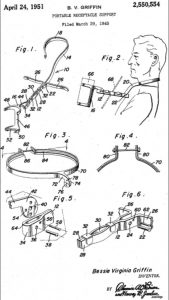

In 1948, Bessie Blount Griffin invented what she called a “portable receptacle support,” a device that supported a feeding bowl, which was attached to the back of the neck of a person who lost control of his arms. Soon thereafter, with the assistance of Theodore Edison (son of the famous Thomas), Blount came up with an easy-to-manufacture disposable emesis basins, those kidney-shaped receptacles for medical waste. Again, nobody in the U.S. showed interest, so she sold it to a company in Belgium, where it continues to be used in hospitals to this day.

And as for the challenge writing with the “wrong hand,” Blount continued to demonstrate how she could write with either hand – or by holding a pencil in her teeth or toes. Believing that others could do the same, she said “You’re not crippled, only crippled in your mind.” She also noticed parallels between one’s physical and emotional well-being and their handwriting. With that knowledge, she wrote a paper on “medical graphology.” Those findings led to her new career as a forensic scientist, where she was consulted by law-enforcement officials and the courts to analyze samples of handwriting. She could also attest to whether a written sample was authentic or a forgery. In her spare time, she took on the task of deciphering barely legible historic documents, including slave documents and historic treaties with Native Americans.

She lived just past her 85th birthday, in 2009. Her inventions will continue to benefit humankind for many years to come.